[Part 1 of the blog adaptation of yesterday’s message at The District Church: “Promise.”]

Remember the 60s TV show, Mission: Impossible, that Tom Cruise successfully shifted to the big screen? Remember that famous line: “Your mission, should you choose to accept it …”?

In Acts 1, we are sort of given a mission by Jesus. In verse 8, he says, “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.”

To unpack this mission and hopefully to help us understand it better, I want to break it down into three parts: “Promised: Power,” “Wanted: Witnesses,” and “Called: Out of Comfort.”

PROMISED: POWER

Here in DC, power is a common concept. Decision-making power. Budget-setting power. The power to craft policies that impact people. We might define power as “the possession of control or command over others,” or the strength to make decisions over (and sometimes against) others. And because it affects others–often drastically, we can shy away from it a little.

But in the Bible, power isn’t portrayed as a necessarily bad thing—and more importantly, power isn’t understood solely as a political concept. For Luke, our author, power is the work of the Holy Spirit. And so Mary is, it says in Luke 1, “overshadowed by the power of the Most High,” and she conceives. Jesus has power as he is anointed by the Spirit of God; he stills the storm with power; he exorcises demons with power; he heals the sick with power; he raises the dead with power; and here in Acts, he tells his disciples, “You will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you.” Jesus has power and he isn’t afraid to use it. Why? Because he understands where it comes from, how it is to be used, and what it is to be used for.

In the prayer of Ephesians 3:14-21, Paul talks a lot about power–only he seems to use it in a different way to how we’d use it. He talks about power to be strengthened by the Spirit, so that Christ may dwell in your hearts; power to grasp how wide and long and high and deep is the love of Christ; power to know this love that surpasses knowledge, so that you may be filled to the measure of all the fullness of God.

Power isn’t simply the ability to bring about whatever you desire, to exercise or effect control over others. True power has a source; true power has a proper exercise; and true power has a purpose—where it comes from, how it is to be used, and what it is to be used for: it is the power of God by his Holy Spirit, working through his people, to see more of heaven come on earth—as it says in the Lord’s Prayer, “your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

This is the power that is promised to the disciples in verse 8. This is the power that is promised to us. This is the power that will change your life and that will make this mission possible.

WANTED: WITNESSES

But Jesus doesn’t just stop with the promise of power. Jesus’ last words are, “But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses …” (v.8)

Last week, for the first time, I was selected for jury duty—picked to be one of the twelve jurors (more on this to come!). In a jury trial, the two sides call their witnesses and they examine and cross-examine these folks, asking questions about what they saw and what they remember happening and were they really sure that’s what happened or did somebody else tell them that’s what happened. It’s on the basis of these witnesses’ testimony, their credibility, and the evidence shown, that the jury is called on to make their decision.

Here in Acts, the Greek word that’s used for ‘witnesses’ carries that same connotation of testifying in legal matters: testifying to what you know, to what you’ve experienced, to the evidence you’ve found, and being credible and trustworthy.

So it is with us: not only are we promised the power of the Spirit, we are also charged to be witnesses in that same legal sense—to testify to the truth, to what we know and to what we have experienced and to the evidence that we have found, and to live our lives in such a way that we are credible and trustworthy as we also speak the truth.

And the truth that we get to proclaim is no less than the gospel: the good news that Jesus Christ is alive, that our sins are forgiven, that a restored relationship with God is possible, and that this God—the Creator of the cosmos—is offering us a mission, should we choose to accept it, that will change the very world we live in.

CALLED: OUT OF COMFORT

But as with any mission in any adventure or story, however impossible it might seem, there is a call—and it is a call out of comfort.

In less than three months’ time, the first installment of the movie adaptation of The Hobbit will come out. In The Hobbit, for those of you who don’t know, the main character is a hobbit—or a Halfling—by the name of Bilbo Baggins. Actually, let’s turn to the first paragraph of the book:

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit. Not a nasty, dirty, wet hole, filled with the ends of worms and an oozy smell, nor yet a dry, bare, sandy hole with nothing in it to sit down on or to eat: it was a hobbit-hole, and that means comfort.

But very soon—in that very same chapter, in fact—Bilbo finds himself agreeing to go on a mission: a very noble mission with great companions and a lofty purpose, a mission in which he will encounter all sorts of weird and wonderful folks—dwarves, elves, wizards—but a mission that seems somewhat impossible and a mission that will take him out of his comfort zone, out of the comfort of his hobbit-hole and take him into places and situations that, if he had known about them beforehand, might seriously have led him to reconsider.

Jesus’ disciples didn’t know what they were getting themselves into when this man approached them and said, “Come, follow me,” but there was something about him that drew them in, something about the way he carried himself, something about the way he talked and the things he said. And now, risen from the dead (as if that weren’t crazy enough!), he comes to them and gives them this mission:

But you will receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you will be my witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth. (v.8)

Jerusalem sounds good: capital city, center of power, happening place. That’s where change will happen—that makes sense; good call. Judea might be the opposite way to where we want to go—that’s away from the decision-makers, away from the influencers of the world. And then, Samaria?!

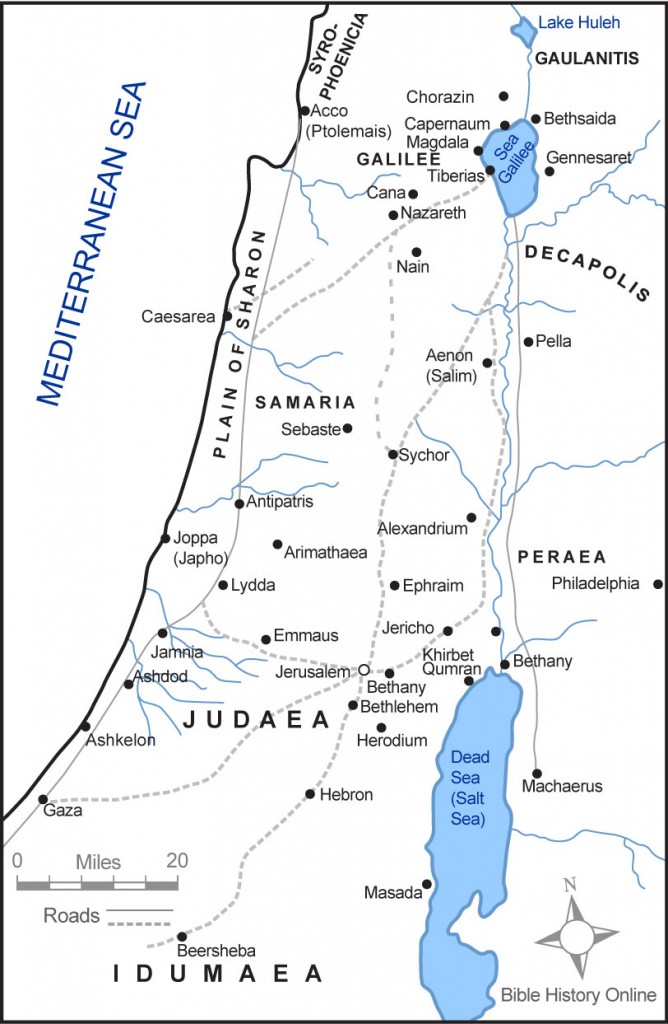

Samaritans and Jews didn’t get along. At all. There were ethnic, cultural, and religious differences between the two, not to mention hundreds of years of animosity and rivalry. Jews looked down on Samaritans as dogs, not even human, not worth interacting with. In fact, if you look at the map above, if they were traveling from Galilee to Jerusalem or the other way, Jews would go around Samaria rather than through it; that’s how much they didn’t get along—which, by the way, makes Jesus’ encounter with the Samaritan woman at the well and his parable of the Good Samaritan all the more powerful, and which makes his instructions to the disciples—his mission—all the more uncomfortable.

And then, “to the ends of the earth.” Even if this is hyperbole and he’s referring to the limits of the known world at the time, it’s a long way. If we look at how far the Roman Empire stretched in Jesus’ day: Egypt, North Africa, modern day Spain, France and parts of Great Britain, Italy, Rome, Greece, Turkey. Remember, the people Jesus chose as his disciples weren’t sophisticated world travelers; they weren’t high rollers or hobnobbers with the movers and shakers of society. At least four of them were fishermen and one was a local tax collector. Moreover, many of Jesus’ followers were women—in those days, not considered the most reliable or credible of witnesses nor the most valued members of society—and yet Jesus calls them too, as it says in Acts 1:14: the eleven apostles were “together with certain women, including Mary the mother of Jesus.” The women were part of this, too. All of Jesus’ followers were given this mission and called out of their comfort zones—out of the comfort of the jobs they knew, the families they knew, the lives they knew, their hometowns, out of the comfort of everything they knew—to be Christ’s witnesses in Jerusalem, in all Judea and Samaria, and to the ends of the earth.

For much of my life, I have struggled and wrestled with the idea of home. I was born an American citizen in Hong Kong, went to an English school in Hong Kong, learning English as my first language, speaking Cantonese at home, going to a Southern Baptist church. At fifteen, I decided I wanted to leave, to explore the wide and wonderful world, and so I headed off—newly baptized—to the UK, where I spent the next eight years, an American (who’d never lived in America) in London. Then, sensing a desire to do something in church—and it wasn’t too much more defined than that at the time—I moved to California to go to seminary; and then after that, discovering a love for politics, I moved to DC to pursue advocacy.

Over the last three decades, with my parents in Hong Kong, my brothers now in Australia and California, and my best friends in London, there has never been anywhere that I didn’t feel at least a little bit at home; but more strongly than that, there has never been anywhere that I have felt completely at home. My journey, like Bilbo Baggins’ and like the disciples’, began a little inadvertently—I didn’t know all of what I was getting into, I couldn’t have foreseen where the road would lead, the relationships it would lead me to and through, the trials and struggles I would encounter, the failures I would endure, the people I would hurt.

Jesus called me out of my comfort zone: God broke my heart for the poor and those in need, and called me to the city—a place of transience—to DC, in fact—the epitome of transience—which, for someone who desires roots, is not the most comfortable thing.

Maybe you can relate: you’ve been faithful, you’ve followed God where he led, and you can say, without a doubt, that God pulled you out of your comfort zone—and it doesn’t just have to be geographic, though it may be:

- you’re from a small town and now you find yourself teaching in an inner city school or working in an inner city hospital;

- you’ve been working hard and for many years on a degree in one area and now you somehow find yourself doing something completely different;

- you’re finding yourself stretched at work or at home or at school—or all of the above—in ways that you don’t know if you can handle;

- you’re in a marriage or a relationship or you’re a parent, and you’re discovering that it’s far more work than you thought it’d be;

- maybe you just realize how much God still has to do in your life—with your heart, with your words, with your thoughts, with your actions, with your soul.

It is not comfortable.

But the good news is that we aren’t called out of comfort—out of our comfort zones—just for the sake of it. Jesus doesn’t simply ask us to give things up that we love or move to a place we don’t know or invest in a city we’re not sure about or make friends with people we wouldn’t normally hang out with or to allow him to do his sanctifying surgery on our lives—just for the sake of it. Jesus calls us out of comfort for a couple reasons:

- So that we might be in the best environment in which to grow. When everything is going your way, when everything is sweet and easy, when everything is comfortable, there’s no reason to change anything, is there? There’s no reason to do anything different in our lives. And when everything is comfortable, we too easily forget the grace and goodness and generosity of God.

- So that he can redefine it for us, and to do so in relation to God. When Jesus comes, he redefines a whole lot of things and helps us understand them as they were meant to be understood. He redefines power as something that comes from God to be used for the purposes of God; he redefines love as a central characteristic of who God is and says, “This is love” and then gives of himself even to death so that others might live; he redefines what it means to be human by living the life that we were made to live. And so also he redefines comfort—true comfort—as something that can only be found in companionship with God and as we choose to carry out God’s mission. I want to call this, “The comfort of being called.”

[To be continued … tomorrow.]

Pingback:The Comfort of Being Called - JUSTIN FUNG | JUSTIN FUNG

Pingback:- JUSTIN FUNG | JUSTIN FUNG